Fish this Spot #1: How to Approach Small Stream Pools

Most anglers can identify the prime holding water along any stretch of stream. Small streams are particularly easy to read since you can usually see whatever structure is present, and if you know how fish like to station around that structure, all you have to do is figure out where to cast in order to get your fly on the fish’s nose. But let’s take that premise a little deeper and look at how to actually work over a pool to maximize catches.

You may ask why this is important. Many folks are perfectly happy with the number of trout they catch. Many would argue that numbers are unimportant, and the older I get, the more I realize this to be true. It doesn’t take catching a ton of trout to have a great outdoor experience. However, the goal is always to get better at whatever we enjoy in life, to improve our skills, perfect our craft, and for me, that means becoming a better fly fisherman.

Over the years I’ve accompanied fisheries biologists on stream surveys of some of my favorite waters. It has always “shocked” me (no pun intended) the number of fish their electro-shocking turned up. Many of our best waters have more trout — and bigger trout — than I ever realized, and I suspect that’s the case with most anglers who fish those same waters. If more anglers knew how many wild trout are present in certain streams, they would frown upon stocking over top of those populations…but that’s a topic for another post.

But it does beg the question…would you still be content catching just 1 or 2 knowing that you could have caught 5 or 6 from that same pool with a little better presentation?

So let’s get started. In this first installment I’d like to discuss a typical small stream pool I fished on Cross Fork. You can read about that outing here: The Cross Fork Experience.

The Approach

This particular pool was situated on a slight bend. A shallow riffle bumped up against a steep bank which created a slight eddy that had washed out a decent-sized hole for such a small stream. The outside of the bend was swift and deep with an obvious ledge running the length of it. The inside bend was a little shallow with not much current. The entire pool was probably 15 feet long and tailed out into a nice riffle. The tail of the pool was slightly wider than the head of the pool.

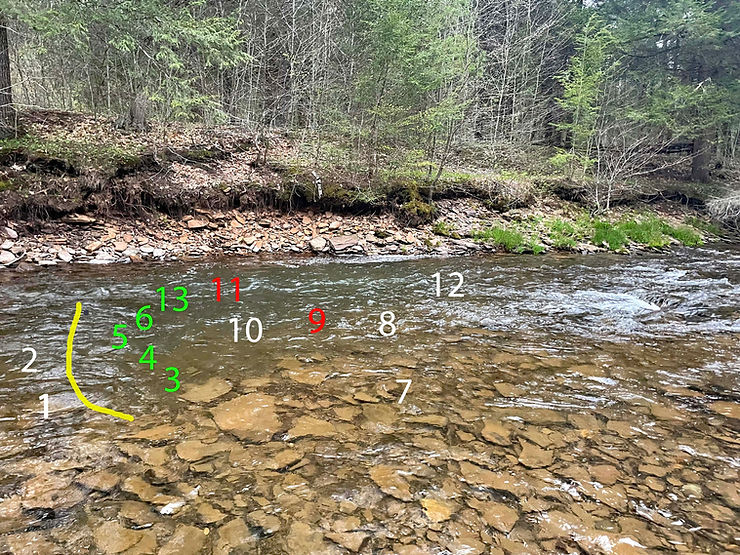

(In the photo: Each number is a fish caught from the pool and the order in which they were caught. White numbers were native brookies. Green were stocked rainbows. Red were wild browns. The yellow line represents the break at the tail end of the pool right where it turned into a riffle.)

Although a few bugs were in the air, there was nothing on the water, and I observed no surface feeding activity at all. This is important to note since I had no risers to actually cast to and simply fished the pool in a methodical manner that could maximize my catch. I was using a size 14 Hendrickson dry fly.

I approached this particular pool from downstream. I intentionally left my first cast short of the tail end of the pool to hopefully pick up any trout stationed in the fast water just below the tailout. I was rewarded with a 5-inch native brookie that inhaled my Hendrickson. My second cast produced a slightly smaller native brookie farther out in the riffle just below the tailout. Nothing else on my next few casts, so I moved up.

Next, I hit the inside bend section of the tailout, just upstream from where it dumped into the riffle. Bam, a 12-inch stocked rainbow! Since the fish took the fly right at the break, I was able to guide it out of the pool without disturbing any other trout that might be nearby.

This is one of the most overlooked aspects of maximizing your catch, I think, and also a great reason for being methodical with how you work a pool. The main reason most fishermen don’t catch more is because the first trout they hook darts throughout the pool and spooks the others. Too much commotion will put down most native and wild trout, especially larger and more cautious browns.

I fished the tailout in the same pattern as I’d fished the riffle below it, slowly working my way across with each cast. Also, I made sure not to land each cast too far upstream into the pool because I didn’t want any trout holding in that deeper water to take notice…yet.

I caught 3 more stocked rainbows from the tailout and was able to pull each one out of the pool and into the riffle as soon as they were hooked. That brought my total for that pool (including the riffle immediately downstream) to 6 trout. This left me with 3/4 of a pool that was still “fresh” with trout that had yet to see my fly.

The inside bend of any river or stream is almost always prime holding water, even if it lacks depth. Trout will sometimes station in water barely deep enough to cover their backs. Or, in the case of this pool on Cross Fork, they will station just off the edge of that shallow water. My first cast landed in water that was barely moving and sat there for a good 5 seconds before a chunky 9-inch native brook trout emerged from the deeper water and traveled a good 5-6 feet to take the Hendrickson.

Observations

I ended up catching 13 trout out of this small pool on Cross Fork, a mix of stocked rainbows, wild browns, and native brookies. Just looking at the numbered photo above, I think it’s interesting that trout number 9 and 11 were both wild browns that came from what I would consider the most prime lies in this pool. If you look at the current breaks, these are the lies where the majority of food in the water column is funneled.

The stocked rainbows were stationed in the second best lies near the tail end of the pool, right above the riffle. Meanwhile, the native brook trout were pushed to the fringes. This is one of the biggest arguments of stocking over wild and native fish, by the way – and especially over top of native brook trout populations: stocked fish and wild browns are more aggressive and will outcompete native brookies for available food. This is just one reason why it’s so important to preserve and conserve streams where native brook trout populations are still strong.

After landing my 10th trout on the Hendrickson, I decided to show them something different. Switched to a black caddis and picked up a wild brown (#11). Switched to a cream caddis and caught another native brookie (#12). Switched back to the Hendrickson and caught one last stocked rainbow (#13) before running out of light.

Thirteen trout is a lot to catch in one small pool. That wasn’t even a stocking point, so it’s not like I was fishing a pool where a bucket of trout had been dumped. These fish migrated to that pool from wherever they’d been stocked.

One last observation about fishing this pool on Cross Fork. That deeper section right in the heart of the pool produced zero trout. Many fishermen, I think, would look at this pool and assume that deeper part of the pool would be the most productive, yet all of the fish I caught were in relatively shallow water. This harkens back to one of the major lessons I learned while watching fisheries biologists electro-shock streams. The majority of the trout they turned up on Class A streams were, in fact, in shallower parts of the stream. Larger pools, where you’d expect to find the highest concentrations, were often barren of trout or produced very few. If I had moved right in and hit that deeper part of the pool first, would I have spooked most of the other fish in the pool and ended up catching a lot less? I think the answer can only be “Yes!”

If nothing else, I hope the numbered photo demonstrates how you can maximize your catch from any stream. Working methodically, fishing the marginal holding waters first and slowly working toward the prime lies, will always produce the most trout from any stretch of water.

What are your thoughts on how I approached this pool? Would you have approached differently? I’d love to hear from you in the comments section below.

Sign up for the Dark Skies Fly Fishing e-newsletter

It's free, delivered to your inbox approximately three times each month.

Sign Up Now

This is among my favorite posts on Dark Skies Fly Fishing! I, too, would love to see more articles like this one that analyze the approach to fishing a specific piece/type of water.

The value I have discovered reading this passage is twofold.

First, I have fished hundreds and hundreds of swift pools just like this one on countless Class A streams. One thing I find myself doing when small-stream fishing is targeting the “best” lie in the pool immediately! My thought is I want to catch the largest fish, a 12″ inch wild brown or 9″ native brookie first instead of hooking the 5″ dink that puts the rest of the pool down while landing him. On larger waters, I would have fished this pool much like you, working the water closest to me and then outward, up, and across. This article has taught me the lesson that multiple good fish can be caught from a single small stream pool and I need to alter my approaches remaining flexible.

For the record, I know I have caught more than one fish from a single piece of small stream water. However, I have never landed thirteen! Impressive!

The second big take-away for me is the positioning of the stocked vs. wild fish. Notice how the stocked fish are stacked in there like cord wood. As if they are in a concrete chute. In contrast, the wild and native fish are spread out uniformly. Are these stocked fish stacked up like that because this is what they know from being raised in a hatchery raceway? Or, are they this way because they are big and aggressive and 3, 4, 5, 6 and 13 is the prime lie where the current is delivering food? And, what does this image exhibit about the displacement of wild fish when stocked fish are placed over top of them? My sentiment is that these stocked counterparts do not play by the rules of a wild trout stream. They are not wild animals that understand the challenges of life in an authentic, natural environment. I feel strongly that hatchery fish need to be kept out of all streams with natural trout reproduction. And, principally Class A streams!

Really enjoyed this one. I would like to see similar treatments of other kinds of structures and scenarios. Aside from the obvious — but often overlooked — point of not pulling a hooked fish through water where others may be holding, insights into how to analyze and pick apart a piece of water is hard-won knowledge that less experienced anglers like me rally value.

Excellent article. It highlights the importance of Observation, Strategy and Stealth.

Great post, and great information, as usual! Like Ed posted, I often am just glad to be out and get so antsy to get into good spots on a smaller stream that I neglect the tails of a good run.

Many times, I run into deeper pools in the Allegheny National Forest on very small streams that I often just pass by, although I’m rigged-up with a dry-dropper, figuring that the re-rig for a streamer isn’t worth it. This has given me a different perspective.

Thanks for the comment, Kevin. Several times, I’ve accompanied biologists on some of those very small ANF streams like the ones you’re probably referring to, and it has always amazed me how big fish will set up in such skinny water. Granted, in some of these really little streams, 15-16 inches is considered a big fish. But still, I’ve seen 20+ inchers feed in water barely deep enough to cover their backs in some of these little streams, too.

Enjoyed the post, I’m always so anxious to get out into the water I don’t always plan my approach. The graphic was very good addition, instead of a narrative it gave the reader a better perspective. Keep up the good posts, I enjoy reading them and I am looking forward to the next one.

I’m with you! Sometimes I just want to get in there and start fishing, lol. There’s always a bit of euphoria to get that first catch under your belt, and after that, no matter what happens or how many you catch, you know it’s going to be a good day!

Thank you for your comments on the post, too. I’ll definitely try to incorporate more graphics with these types of post in the future. Like you, I enjoy it more with a visual aid.

Great post. It is true when bugs are active the trout move into surprisingly shallow water. Last May when I was in Potter and isos were hatching the largest wild browns were in the very top and bottom of the pools. It was fun alternating between a large dry and a nymph, 12 – 18 in below an indicator. Probably should have done the dry/dropper thing.

Thank you for your comment, William! You’re right, when active, they prefer the shallow water. Most of the time, if they’re deep or hugging the bottom, they’re just “resting” and inactive, and although you can still catch them, you basically have to knock them on the noggin to get them to hit. Do you like the dry-dropper? I’m not a fan of it, to be honest. It’s effective, but not my favorite way to fish. I guess I’m a “one or the other” type of fly fisherman.

I tend to agree and I only really use the dry dropper out west. I had really good luck with the rig on the Stillwater. Many years ago I fished a sulphur hatch on Spring Creek with PT nymph under the dun and caught way more of the rising fish on the nymph.

The weather looks great up your way. We are in a drought with unfavorable water temps and the Delaware is really low, but I’m sure the smallmouths and juvenile strippers are on in the morning and evenings.