Sara Jane McBride: Pioneering Entomologist and Fly Tier

Author’s note: This is an expanded version of a piece previously published in the Summer 2024 edition of Dark Skies Fly Fishing Magazine and which contains newly discovered details about Sara J. McBride’s mysterious life.

In 1875, Sara Jane McBride was about 31 when she confidently took over her late father’s tackle business in Mumford, New York. She made a splash as an early professional women fly tier and was one of the first in America to link entomology with fly tying, publishing on the concept of “match the hatch” decades before it became widely popularized. Just five years after her rise, she disappeared.

Sara J. McBride was the eighth of 11 known children of John and Mary H. McBride, Irish-born residents of Mumford in Western New York State. In his younger days, John McBride apprenticed as a salmon fisherman on the River Shannon in Ireland, learning fly tying and angling techniques. After he immigrated to the United States, John opened a fishing tackle business in Mumford and gained a national reputation for high quality imitation flies. John’s daughter Sara Jane, born about 1844, was the only one of his children known to have taken an interest in the tackle trade. As a teen, she began tying flies with her father. By the time of his death, she was an expert, apparently the primary tier of the “celebrated McBride flies” for which her father was famous.

In Great Britain and Europe, fly tying and entomology, or the study of insects, had long been linked. Foundational books such Albert Ronalds’ The Fly-fisher’s Entomology (1836) explained insect life cycles and offered lure patterns that imitated British trout’s favorite insect prey. These fly patterns traveled to North America with immigrants, where favorite recipes were replicated and adapted. Simultaneously, “fancy flies,” what we would now recognize as “attractors,” were all the rage in North America, relying on wild colors and shapes to entice fish rather than trick them.

Unlike in Great Britain, no consummate scientific works had been published on entomology for the American angler by the mid-1800s. Insects native to North America are different than those in Great Britain, and scholarship regarding trout feeding behavior in American waters had not been compiled. The concept of “match the hatch,” or using specific lures when particular insects were most prevalent, would not be widely popularized in America for about 80 more years.

The McBride home in Mumford was not far from Spring Creek, then known as Caledonia Creek. The stream’s fresh, lively water and shaded banks made it a perfect habitat for native brook trout. Generations of anglers have fished Spring Creek for recreation and livelihood, and throughout the nineteenth century, several tackle businesses and fisheries took advantage of the area. Best known is the New York State Fish Hatchery in Caledonia, established in 1864 by Seth Green, and the oldest hatchery in the western hemisphere.

As a young person, Sara McBride observed and presumably fished Spring Creek with her father. She watched as batches of insects emerged throughout the seasons, took notice of trout behaviors, and measured environmental conditions. She dissected trout, identifying their last meals. To observe the stream fauna’s life cycles and habits more closely, McBride kept aquariums. This scientific work, somewhat unusual for a woman in the nineteenth century, was foundational.

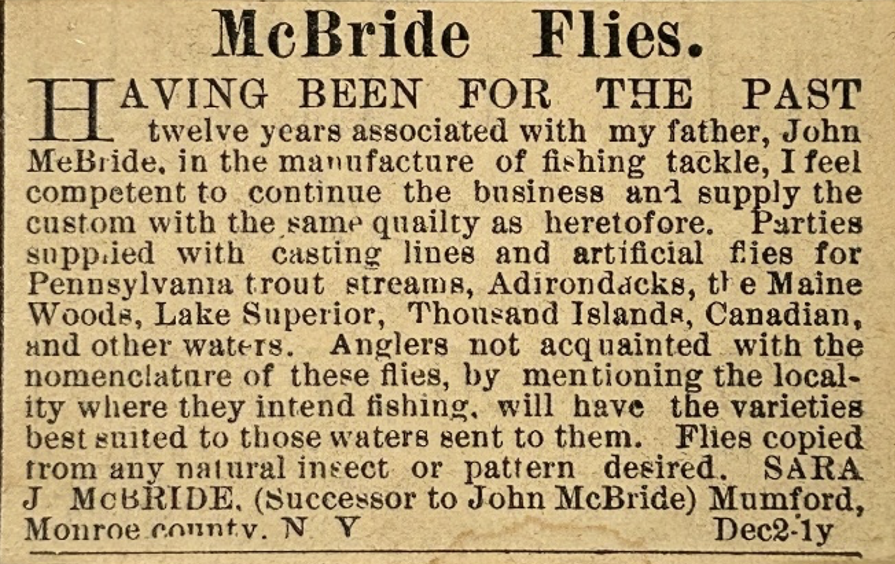

When John McBride died, in 1875, Sara Jane announced that she would continue the tackle business, supplying customers with excellent imitation flies. Fly tying requires nimble and careful work, and became more common for women by the end of the 1800s. In the 1870s, however, Sara Jane McBride became one the earliest professional woman fly tiers in America. An article proposed that “few men can manipulate the delicate feathers and tinsel with the same delicacy and artistic effect as Sara McBride.” Additionally, she offered to recommend imitations of native insects to anglers across the East Coast, indicating her familiarity with stream biology

In early 1876, McBride published “Metaphysics of Fly Fishing,” a three-part article, in Forest and Stream. The magazine, a precursor to today’s Field and Stream, explicitly advocated fishing, hunting, and outdoor exploration for both men and women. The editor, Charles Hallock, praised McBride’s articles as the first-ever published entomological works geared toward American anglers.

Throughout 1876, Sara J. McBride was regularly mentioned in Forest and Stream, including in a discussion of barbless hooks, which she endorsed. Advertisements by the Sportsman’s Emporium in New York City proudly announced their status as “sole agents for the celebrated McBride Flies.” The ads demonstrate brand familiarity and the lures’ widespread success.

Following the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, the first official world’s fair, editor Hallock published a notice in Forest and Stream celebrating McBride’s bronze medal win in the fly-dressing category. The award recognized McBride’s fly tying skill, which Hallock attributed to her careful study of entomology and the artistic ability required to make imitations of real insects.

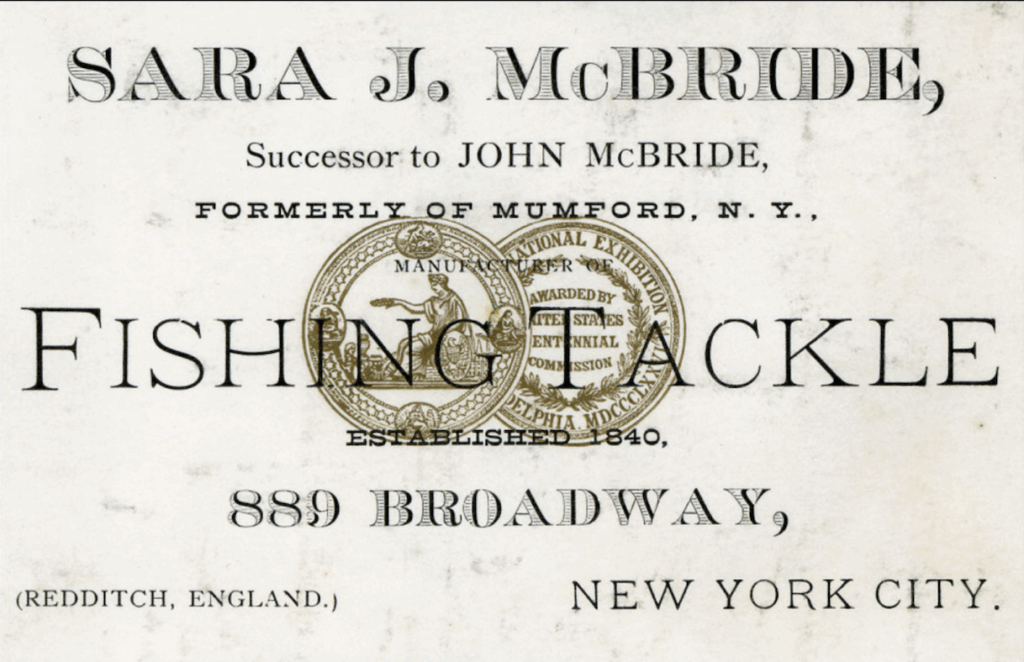

In early 1877, Sara McBride moved her tackle business from Mumford to New York City. The advertisement for her new shop on Broadway built on the reputation of her father’s 30-year business and listed an array of fishing tackle. Notable was the offering of fly-tying materials “supplied to amateurs,” suggesting that the industry was opening to do-it-yourselfers and was receptive to experimentation and accessibility. McBride also mentioned that she was connected with Redditch, England, where the world-renowned Allcock tackle factory was based.

In early 1876, McBride published “Metaphysics of Fly Fishing,” a three-part article, in Forest and Stream. The magazine, a precursor to today’s Field and Stream, explicitly advocated fishing, hunting, and outdoor exploration for both men and women. The editor, Charles Hallock, praised McBride’s articles as the first-ever published entomological works geared toward American anglers.

Throughout 1876, Sara J. McBride was regularly mentioned in Forest and Stream, including in a discussion of barbless hooks, which she endorsed. Advertisements by the Sportsman’s Emporium in New York City proudly announced their status as “sole agents for the celebrated McBride Flies.” The ads demonstrate brand familiarity and the lures’ widespread success.

Following the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, the first official world’s fair, editor Hallock published a notice in Forest and Stream celebrating McBride’s bronze medal win in the fly-dressing category. The award recognized McBride’s fly tying skill, which Hallock attributed to her careful study of entomology and the artistic ability required to make imitations of real insects.

In early 1877, Sara McBride moved her tackle business from Mumford to New York City. The advertisement for her new shop on Broadway built on the reputation of her father’s 30-year business and listed an array of fishing tackle. Notable was the offering of fly-tying materials “supplied to amateurs,” suggesting that the industry was opening to do-it-yourselfers and was receptive to experimentation and accessibility. McBride also mentioned that she was connected with Redditch, England, where the world-renowned Allcock tackle factory was based.

Shortly after her move to New York City, a spat with the Sportsman’s Emporium was silhouetted in the pages of Forest and Stream. From her Broadway store, McBride submitted a notice stating that she removed all her flies from the Nassau Street gear shop, contrary to their recent advertisements. The owner shot back hotly in his defense. Evidently, since her move to New York, Sara J. McBride no longer needed an agent in the city. Before long, the Emporium was advertising flies “tied after McBride…patterns,” invoking the brand familiarity to imply quality.

Sara McBride’s presence in New York City was short-lived. She announced a return to Mumford only 18 months after her New York City shop opened. McBride continued advertising flies and tackle from her hometown, and then from nearby Caledonia, without explaining why she left New York.

In late 1880, McBride visited the Allcock tackle factory in Redditch, England, writing a cheerful essay on the experience, which was published in Forest and Stream. This is her last known published article. The last mention of her in Forest and Stream her is a one-sentence note in 1884, stating “Miss Sarah McBride is not making flies now. She is in Australia.” And with that tantalizing clue, McBride vanished, leaving historians to busily revisit resources for decades, hoping for a new lead. Many theories circulated about why she seemingly left the industry and what happened to her.

Recently, in 2025, the author of this piece uncovered records detailing a surprising and tragic twist, finally answering the question of what happened to Sara J. McBride.

The new information, buried in digitized US Department of State documents, shows that McBride spent time with W. L. Hoskins, an old friend of her father’s, in Owego, New York, before making her trip to the Allcock tackle factory. From England, she traveled by boat to Australia, eventually renting a cottage in Townsville, Queensland, where she worked as a music instructor. Her most valuable possession was a piano.

On September 28, 1885, correspondence indicates that McBride was transferred from the Townsville jail to Goodna Asylum for the Insane in Brisbane, Queensland. No documentation has been found about what precipitated her detainment. Most of her personal effects were supposedly sent to her, but over the next two years, she agreed to have her meager list of household items, plus the piano, sold at auction. The money would help pay her former landlord and the US consul in Townsville who had acted on her behalf.

A few pieces of correspondence written by Sara McBride and others show that she considered herself sane and resented being confined. Writing from Goodna, she requested help from her old friend W. L. Hoskins in Owego. Hoskins revealed in correspondence that he thought she was “queer and eccentric in manner,” but that he “[did not] think her crazy by any means.” At the time, the term “queer” usually just meant “odd” rather than carrying a connotation of sexual identity.

McBride’s plea for discharge moved up the ranks in the United States, reaching the Department of State by early 1889. Secretary of State Thomas F. Bayard’s correspondence on the matter suggested that, given the facts, her discharge “could not be demanded as a right,” and there were no funds to support her voyage home. A final entry from a consul in New South Wales, Australia, who was investigating the situation, stated that it was “not advisable to give her liberty,” though he suggested the institution was interested in sending her home to friends in America. From the information discovered, however, it seems that no further attempts were made to discharge McBride from Goodna.

By 1900, when Sara McBride was about 56 years old, she was transferred to another asylum, the Willowburn Mental Asylum, later known as Toowoomba Mental Hospital. Sadly, she lived there for almost four more decades, passing away on January 14, 1938. Her only possessions of note at the time were a broken gold watch and a brooch. Both were sold, since the hospital was not aware of any living relatives. She was buried at the nearby Drayton and Toowoomba Cemetery in Toowoomba, Queensland, Australia.

Despite the resolution of the decades-old mystery of Sara Jane McBride’s disappearance, a multitude of new and complex questions arise. Was McBride suffering from mental illness for the second half of her long life? Perhaps, given the ideas at the time, there was something about her “queer and eccentric manner” that others simply didn’t understand. From her life’s trajectory, it appears that she likely did not fit the typical mold for a Victorian woman, and she faced unjust hardship and tragic circumstances, possibly as a result of her differences. These events represent a heartbreaking loss of creativity and talent, including any further contributions she might have made to the fields of entomology and fly fishing.

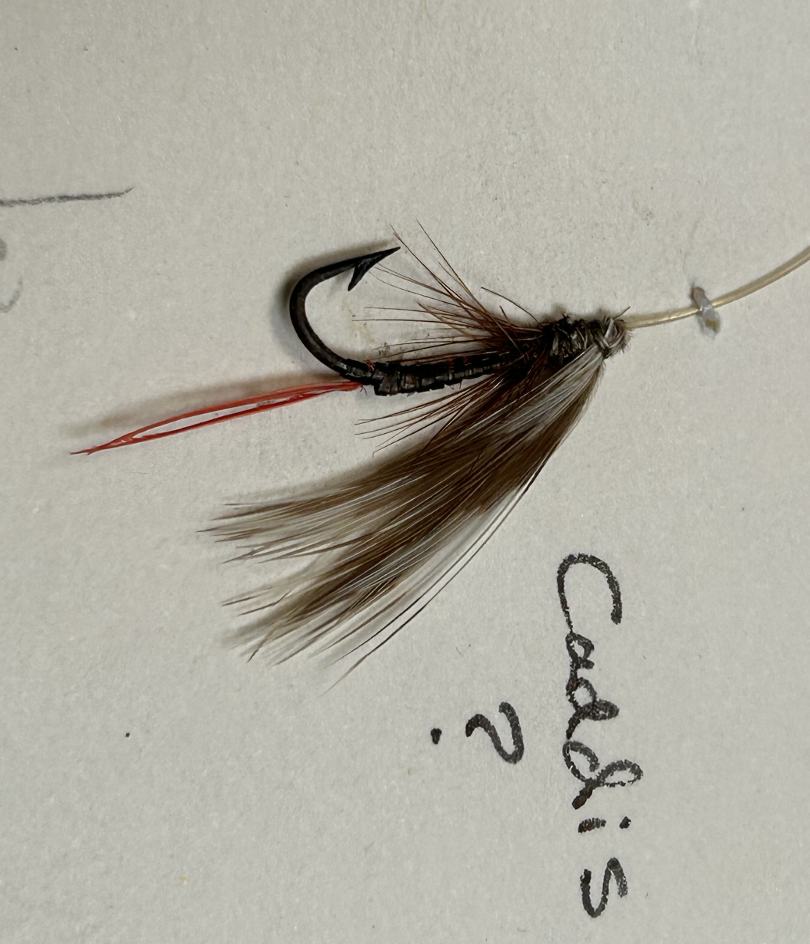

Despite McBride’s short and mysterious career, she left a mark on fly fishing. In Mary Orvis Marbury’s Favorite Flies and Their Histories (1892), an encyclopedia of American lures compiled from country-wide submissions, several patterns and recommendations are credited to Sara J. McBride. According to Marbury’s book, the flies allegedly originated or popularized by McBride are the Portland, the Hod, the General Hooker, and, perhaps most famously, the Tomah Jo, a salmon fly.

Regrettably, after the late 1800s Sara McBride’s contributions were largely forgotten and others were credited with work that she pioneered or popularized in the 1870s. McBride’s entomological essays encourage anglers to focus on dry flies, yet Frederic Halford and Theodore Gordon are remembered as “fathers” of dry-fly fishing. Ernest Schwiebert’s classic book Matching the Hatch (1955) widely popularized the concept of using particular imitation flies during insect hatches. Although Sara Jane McBride is believed to be the first to publish on this subject in America, she is not mentioned in Schwiebert’s literature review.

As one of the first professional woman fly-tiers in the United States and an author of pioneering American entomological literature for anglers, McBride deserves credit for her contributions to the field. Although her career was brief, her work directly and indirectly impacted the development of fly-fishing techniques, concepts, and even flies that we still use today. Along with Seth Green’s hatchery and other fishing businesses on Spring Creek, Sara Jane McBride’s legacy is part of the vibrant fishing heritage of Mumford and Caledonia, and a piece of North American fly-fishing history, too.

Please contact the Livingston County Historian’s Office, NY, at www.livingstoncountyny.gov with any questions or comments about Sara Jane McBride and the fly-fishing industry in Caledonia and Mumford.

Have a fly fishing question you’d like answered? Drop us a line at info@darkskskiesflyfishing.com! If we use your question in a blog post or in the newsletter, we’ll send you a FREE fly box with a dozen of our favorite nymphs and dry flies!