Ed Shenk: Professor of the Letort

Ralph Edward “Ed” Shenk was born in January 1927 and grew up not far from the banks of Pennsylvania’s famous Letort Spring Run. When Shenk was a kid, he was asked about the fishing on Letort Spring Run one first day of trout season. “Really good!” he said, “I caught a couple of dandy eight-inchers and some little ones, too.”

It was typical Shenk, enthusiastic and good-humored, and happy to be on the stream. With tongue mostly in cheek, one of Shenk’s contemporaries, Joe Humphreys, says, “I didn’t like Ed at first; I didn’t like anyone who could out-fish me.”

Humphreys, who taught fly fishing at Penn State University for 19 years, continues, “He was the best fly fisherman I’ve ever seen. A lot of guys talk a good game. Ed Shenk was the game.”

Shenk and Humphreys eventually became close friends, teaming up to teach fly fishing classes for 38 years at Allenberry Resort in Boiling Springs, PA. They worked well together. Humphreys had the flamboyant personality that drew crowds, while Shenk did whatever Joe asked of him, gladly playing a supporting role. But don’t take that to mean Ed Shenk wasn’t opinionated about fly fishing. He was known to speak his mind. In 1980, when a group of fly fishers were invited to Camp David to teach President Jimmy Carter about fly fishing, Shenk had no problem telling the president, “Your casting stinks.”

“Ed Shenk had a great sense of humor,” says Joe Humphreys, “but he always told you exactly what he thought about something, and he was usually right.”

Shenk published only one how-to book on fly fishing but was a prolific magazine writer. He wasn’t a perfectionist, and, in fact, believed that too much time was wasted on trying to be perfect in the various facets of fly fishing. His flies exemplify his opinion on the matter. Although he could tie magnificent-looking patterns, he personally preferred to use messier, less exacting versions that wouldn’t meet the standards of most fly shops.

Shenk volunteered often and enjoyed teaching people to fly fish, but he was happiest when prowling the banks of Letort Spring Run. Prior to his passing in 2020, Shenk spent thousands of hours over a 90-year span plying his home waters for big trout. Some of those trout were legendary, and one of them in particular became world famous, but more about that later.

An Innovative Fly Tyer

Ed Shenk loved details, and the opening chapter of his book, Fly Rod Trouting (1989), describes Letort Spring Run with the precision of a cartographer. Mapmaking was Shenk’s profession, and he created topographical maps for the U.S. Geological Service (USGS) for 10 years before working as a land planner for another 27 years. Each paragraph in Shenk’s first chapter outlines, with remarkable accuracy, every twist and turn and hideout where big trout often lurked in the famous spring creek. Every distance between pools is measured, every width of the stream calculated, in exact feet.

Many times, as anglers are apt to do in conversation, Shenk would hold his hands apart to show the length of whatever big trout he’d caught or was trying to catch. Occasionally someone produced a measuring tape to verify the distance between his palms. There was never any exaggeration. If Ed Shenk said a fish was 23.5 inches, then it was 23.5 inches.

Shenk was a skilled sketch artist and supplied the art for many of his articles. An eye for detail and proportion helped him at the fly tying bench, too, as he created numerous patterns that are still popular today, such as the Cress Bug, Letort Cricket, and Letort Hopper, the latter not to be confused with Ernest Schweibert’s fly of the same name. The two Letort Hoppers were developed in the late-1950s, their near-simultaneous creation was purely coincidental; neither man knew of the other’s designs. There were a few minute differences in the flies, but the main one was wing placement; Shenk tied the wings flat on top of the body whereas Schweibert’s were tent-shaped, akin to those on the Joe’s Hopper.

The Double Trico Spinner was one of Shenk’s most original creations. By “stacking” two Trico Spinners on the same hook to imitate mating flies, he could tie the fly on a size 18 instead of a size 22 or 24. Many aging anglers’ eyes appreciate this.

Although Shenk didn’t invent the dubbing loop technique, he definitely popularized it in his magazine articles. Many of his patterns utilized the dubbing loop and required trimming to shape, a practice first developed by Shenk. This gave the flies a translucency and softness that made trout want to chomp and chew on them rather than spit them out, which the educated browns of the Letort had a tendency to do.

Two streamer patterns, in particular, rank as some of Shenk’s best work: Shenk’s White Minnow and Shenk’s Sculpin, sometimes referred to as “Old Ugly”. Along with Joe Brooks’ writings regarding the Muddler Minnow, Shenk helped popularize the use of sculpin patterns throughout the 1960s, even coining the term “sculpinating” to describe this method of fly fishing.

Both of Shenk’s sculpin patterns were tailor-made for Letort Spring Run, a stream with a smooth, sandy bottom. Shenk liked to place a small weight on the tippet near the eye of the hook and jig the fly along the bottom as it drifted downstream. It was, in a word, deadly, and it’s a technique that has found its way back into the fly fishing mainstream in recent years with patterns such as the Balanced Leech and jig-style streamers.

Streamer afficionados owe a debt of gratitude to Shenk, not just for the patterns he innovated, but for the ones he promoted, too. In the mid-1970s, Shenk took two teenagers together on their first trip to Montana. One was Bill Skilton, who became a longtime contracted tyer for Orvis and is now well-known for producing some of the finest fly-tying hackle in the industry, and the other was Barry Beck, whose articles and photography have graced fly fishing magazines for over 40 years.

On that trip, Beck, who worked at a fly shop near Benton, PA, brought along a new pattern for them to try on Western waters. Shenk and crew stopped at every shop they crossed, demonstrating how to tie the pattern and vouching for its effectiveness. The tyer who developed the pattern was Russell Blessing, and the fly was the now-ubiquitous Woolly Bugger.

Professor of the Letort

In 1951, Ed Shenk married Frances “Tommy” Bailey and moved into a house on a street that intersected A Street in Carlisle, just down from where he was born. They were married 50 years and had four children: Stephen, Diane, Susan, and Patricia. Shenk attempted to teach his kids the art of fly fishing, but none of them had the passion for it like Ed did. In fact, one Sunday after church, Shenk took his son to Letort Spring Run and handed him a fly rod and said, “Now throw it in.” Taking his father’s instructions literally, Stephen did as told and threw the rod into the water! Shenk stripped down to his underwear and waded out to fetch the rod.

For many years, Shenk worked in Arlington, VA, returning home on weekends to see his family, and fish. The long hours and time away made him weary, until he eventually quit his job with the USGS and opened a fly shop in his basement with long-time friend Ed Koch before finally taking a job as a land planner. Proximity to his beloved Letort was paramount to him.

Michael J. Klimkos, who has written numerous books about Cumberland Valley streams, has said that, while Charlie Fox was known as the “Dean of the Letort,” Ed Shenk was certainly a tenured professor. If there was a big brown in Letort Spring Run, Shenk likely knew about it. One such fish was a 27.5-inch, 9-pound brown caught in August 1962 by Koch on a dry fly. As Shenk later told Humphreys, Shenk hooked that trout the evening before and played it nearly to exhaustion. But when he tried to drag the fish up over some weeds to net it, his line tangled in the elodea and broke. Upon learning of Koch’s catch the next day, Shenk joked that Koch only landed the fish because Shenk had already played it almost to death.

That was a time of great comradery and innovation in fly fishing, and the anglers of central Pennsylvania led the way. A group of anglers, known as the Letort Regulars, gathered weekly at Charlie Fox’s hut on the banks of Letort Spring Run and other venues around Carlisle. The regulars included Shenk, Fox, Tommy Thomas, Ross Trimmer, and others, and they frequently welcomed visitors such as Lefty Kreh and Joe Brooks any time they were passing through the area. Bob McCafferty donated a fly tying kit that stayed at the hut, and hours of conversation and experimentation sparked new ideas and methods for tying flies that might fool trout in Letort Spring Run, one of the toughest streams in the country in which to consistently catch trout. This brought about two assumptions: first, if you could catch trout in the Letort, then you could catch trout anywhere; and second, if a fly worked on the Letort, then it would work anywhere.

Good luck trying to disprove either point.

Incidentally, the hut on Fox’s property became known as “the 19th Hole.” It was there, on May 23, 1969, that the Cumberland Valley Chapter of Trout Unlimited was formed, with Ed Shenk and Jim Bashline elected co-presidents. When asked in an interview later on why the organization needed two presidents, Shenk replied, “I didn’t want to be president and neither did Jim. But we decided we could both do it together.”

Master of the Short Rod

Shenk’s love of short fly rods, especially those measuring six feet or less, was a result of two factors. First, Letort Spring Run was, technically speaking, a small stream, where a cast beyond 40 feet was seldom needed (or advised, given the creek’s complex currents that infamously induce drag). And second, as Shenk explained in Fly Rod Trouting, magazine photos of his hero Lee Wulff “with a hand-tailed salmon in one hand and a short bamboo rod in the other fired the imaginations of many fishermen, including this one.” If short rods were put to such effective use by Lee Wulff, Shenk figured, they were good enough for him.

One inherent benefit of using a short rod was that it forced Shenk to perfect his casting abilities. “His accuracy was incredible,” says Joe Humphreys. “He could drop a fly within a quarter-inch of structure time after time after time, from any distance.”

Of course, that didn’t prevent many of his peers, including Humphreys, from giving Shenk grief over his short rod fascination. “I told him I use a longer rod because I can get more distance, reach out over tricky currents, and get better drag-free drifts. I said, ‘I don’t understand why you don’t use a longer rod,’” recalls Humphreys. “His response was superb. He said, ‘I know these things are true, and I know you have an advantage, but I just enjoy fishing short rods.’ And then he said, ‘Besides, it’s better than fishing with that telephone pole you’re using!’”

In Fly Rod Trouting, Shenk explains, “To me, a large part of fishing and hunting is aesthetic. A diminutive fly rod, neatly done, with a tiny grip to match and a plain reel seat is a joy to look at and carry, as is a short, slender, light-weight shotgun or rifle.”

Signature Fish

Ed Shenk had a knack for locating big trout. He was a big trout hunter before the term became popular, but his success catching them was more than luck. It derived from years of observation and figuring out that big brown trout had patterns, and if you paid close attention and were persistent, you could put yourself in the right place at the right time. The story of Old George is a classic example. Rarely throughout history has the reputation of an angler and a fish been so intertwined as it is with Shenk and this leviathan of the Letort.

Shenk discovered Old George one day in 1962 when he was reeling in a 10-inch trout and the large brown emerged from under a brush pile to claim the smaller trout as its own. What followed was a three-year obsession and countless days spent crouched down in the streamside vegetation waiting for Old George to appear. And the trout always did. Each evening, shortly before dark, the giant brown left its home pool and swam some 75 yards downstream through a long stretch of shallows to its feeding lie. The trout would overnight there before heading back to its home pool, at 5:45 on the dot, the next morning.

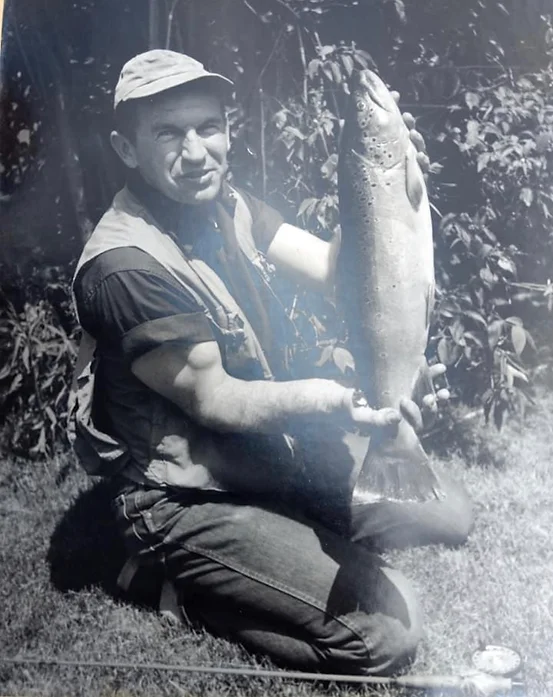

Shenk hooked Old George on five separate occasions, four of which ended in heartbreak. He finally landed the fish on May 14, 1964, on a white marabou streamer and a 5-foot fiberglass rod. As it turned out, Old George was a lady, and the big female brown measured 27.25 inches and weighed 8.5 pounds. Shenk immediately drove down to Charlie Fox’s hut to show off the fish.

“Old George was a Lady” became one of Ed Shenk’s most beloved stories. Its publication inspired many anglers in much the same way that Shenk had been inspired by Lee Wulff. At the end of the story, which is included as the final chapter in Fly Rod Trouting, Shenk reflects on the three years spent trying to catch the fish: “I am pleased that I was finally able to outwit and land Old George; but I get a funny feeling every time I look into the pool the big fish called home. Somehow I still expect to peek over the bank and see the wonderful shape of that great old fish gently finning in the crystal clear current. I’m sorry that I never will again.”

Deservedly, Ed Shenk, who passed away in 2020, was inducted into the Fly Fishing Hall of Fame on October 6, 2012, at the Catskill Fly Fishing Center and Museum in Livingston Manor, New York.

This article first appeared in the July/August 2023 issue of American Fly Fishing.

I owe a debt of gratitude to all those who helped bring this article to fruition, whether with stories and anecdotes about Ed Shenk, phone interviews, photos, access to archives, and other information that helped make this one of my favorite articles I’ve ever written. These people include Shenk’s daughters, Patricia Williams and Susan Shenk, Bill Skilton and the Pennsylvania Fly Fishing Museum in Carlisle, Michael J. Klimkos, Thomas Baltz, and of course the inimitable Joe Humphreys.

great article Ralph. you really captured the spirit of man.

Thanks, Doug! It took a lot of research and help from a number of people to bring this together, so it means a lot for you to say I captured the spirit of the man.

Hey man i am 12 years old and just figured out my grate grandfather was a legend and i love the article of him.

Yes, he sure inspired a lot of fly fishermen, myself included. Really glad you enjoyed the article.

First time I have seen this article about my Dad. Thank you so much. And I did quite a bit of trout fishing, by the way.

Stephen Shenk, Columbus, GA

Hi Stephen, thank you for dropping a line. I really appreciate it. Your dad and his writings inspired many fly fishermen, myself included.

Ralph