Fish this Spot #2: How to Approach Junction Pools

Junction pools are formed wherever two bodies of moving water converge, such as the famous “Junction Pool” where the Beaverkill and Willowemac join in the Catskills. It is said that “Junction Pool is thought to possess strange and mystifying currents, causing migrating trout to linger for days while they try to decide which stream to follow.”

Indeed, junction pools can be difficult to fish, mainly due to so many conflicting currents. Although every junction pool is different, they do have some similarities in regards to the prime lies within each section.

Dissecting Junction Pools

The best way to learn how to fish junction pools on large streams and rivers is to visit a small stream where you know similar pools exists. Find a place where the water is low and clear enough to see the bottom and study the layout of the stream bed.

First, take note of where the ledges occur. Hint: they’re typically at the head of the pool on the main stem side, right where the water dumps into the pool. Tributaries that come in on a more perpendicular angle basically help cut out that ledge, which will typically be the deepest part of the pool, too. Although every situation is different, and no two streams are the same, this feature seems pretty consistent.

Second, take note of how the currents come together and where the seams are located. If there are rocks or some other type of structure, pay attention to how the currents play around that structure.

Third, the more perpendicular the streams are where they join, the more likely you’ll get that whirlpool effect, which can basically wash out a big bowl-shaped pool. In these cases, I usually find steep drop-offs on each side.

Fourth, the tailout of the pool is especially important to note. When feeding, such as during hatches, many fish will leave the deeper parts of the pool and stage in the shallower tailouts.

It might be worth noting that junction pools created by rivers of similar size that converge at gradual angles may not have distinct, carved-out ledges. For instance, where First Fork Sinnemahoning Creek and East Fork Sinnemahoning Creek meet, there’s hardly even a pool because the streams run almost parallel for about 50 yards before joining. These streams mesh almost seamlessly together.

However, junction pools formed by streams or tributaries joining at nearly-perpendicular angles will always provide good holding water for trout as long as each stream has enough volume and current to continuously wash out a deep pool. So if you’re targeting new streams and rivers and want to get on fish right away, look at a map and find those places where tributaries join the main stem at perpendicular angles. You’ll almost always find a deep pool with good structure there, and there will almost always be trout present.

Example #1 – First Fork Sinnemahoning Creek and Southwoods Branch

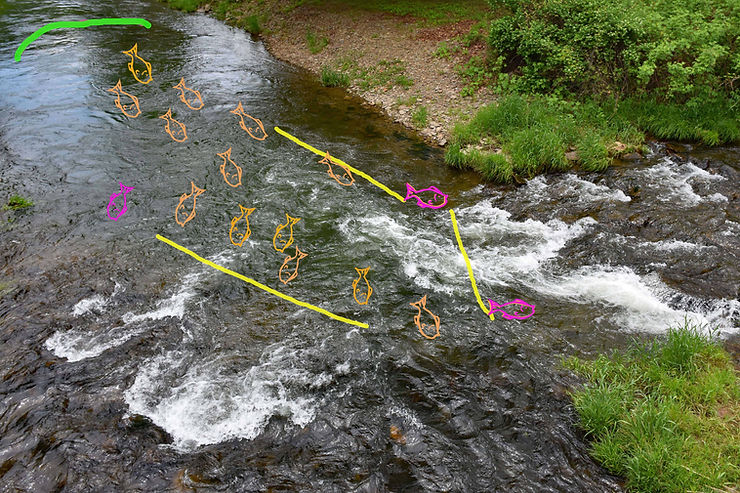

This photo shows where two streams converge, First Fork (on the left in the photo) and Southwoods Branch (on the right in the photo). In this example, where both streams are nearly equal in size, although First Fork is slightly larger, ledges (the yellow lines) are created in multiple places. Naturally, these will be hot spots.

Another hot spot is immediately downstream of the most turbulent water in the pool, right where the water begins to flatten and where the tailout begins. From here to the bottom of the pool where it empties into riffles, fish will stage when feeding.

More hot spots are in the seams at the head of the pool. I know this graphic is rudimentary, at best, but hopefully it helps you visualize how most trout will hold in these situations.

But notice the three fish outlined in pink. These fish are generally overlooked in junction pools. Most anglers, I think, focus on the deeper water, and for good reason – that’s where the majority of the trout are going to be. But they often forget to hit these little corners. Compared to the rest of the pool, these corners are shallow and don’t look like much. Truth is, these are typically calm spots, out of the main current, where food will naturally gather and make for easy dining for trout.

Example #2 – Pine Creek and Genesee Forks

I fished this particular junction pool several times last spring. Pine Creek enters from the west and Genesee Forks enters from the north. This section got pounded all spring. I know because I drive past it almost daily. Given that it had been fished so hard, I wasn’t expecting a whole lot my first time there, so I was pleasantly surprised to find a number of trout still in there. I had a blast, catching 11 in a little over an hour. Each orange “x” represents the location of one of the trout I caught that day.

The photo above is from Google Earth and appears to have been taken during the summer months, during very low water. I liked this image because it provides an aerial view of exactly where the ledges and drop-offs occur, right where the brown and green colors meet. Again, the yellow lines indicate where the ledges and drop-offs occur.

I didn’t even bother fishing from the bank on the right side of the stream, which is where 90% of people fish it according to the heavy paths leading down to the water and the piles of empty worm containers and Power Bait jars lying around. In fact, while I was there, several folks stopped by and started fishing from that bank. The green circle represents their actual “range” as far as where they’d have the best opportunity to catch fish. As you can see, they’re missing almost all of the trout residing on the west side of the stream. None of them caught anything and they soon moved off downstream. In fact, in the dozens of times I’ve driven past that pool, I’ve never seen anyone fish it from the west bank.

(Photo: Here’s a photo of this junction pool from the side of the stream where people most often fish. From this vantage point, it’s easy to see why people weren’t having much luck. Too many currents pulling their presentation through the best water before trout even had a chance to see it.)

Many people do fish from the tail end of the pool, though, but for whatever reason, they seldom cross the stream and come up the west bank. They almost always fish it from the east shore. In this case, even changing positions downstream still means they’re missing a lot of trout. Later in the season, when water levels drop and those mid-stream currents aren’t so turbulent, they’ll have better access to almost all of the prime spots throughout the pool.

So why don’t they adjust their position or cross the stream to get to the best lies? One reason could be because the water is deep near the east bank, just off the rock from where this photo was taken. There’s a little whirlpool here where fish definitely stack up. However, because this section gets fished so heavily, trout get picked out of here first.

Another reason why they don’t adjust is simply because of where the most worn paths are along the stream. People tend to fish where others fish. If there’s a worn path or worn spot where people have stood to fish, it’s very likely that the majority of the people who come across that pool will also fish it from those worn spots. We are, after all, creatures of habit.

No Two are the Same

As mentioned earlier, no two pools are the same. Many factors can influence how a junction pool is carved out. These are just two examples of the many junction pools I fish every year and how I approach them.

In short, look for the edges – where shallow water meets deep water, where fast water meets slow water, and all those little nooks and crannies in between. These are the places where feeding trout like to stage in junction pools.

Getting your fly to those fish in a natural, drag-free manner is a whole other topic. It takes practice, taking note of how and where the current takes your line, and then making the necessary adjustments to try to get your fly to drift through those prime lies. But step number one is identifying those prime lies, and I hope this article has provided at least a few insights into how to do that.

Sign up for the Dark Skies Fly Fishing e-newsletter

It's free, delivered to your inbox approximately three times each month.

Sign Up Now

One more observation. In the graphic above of the First Fork junction pool, the fish exhibited in pink are in the exact seams that I like to target!

This article is crazy informative. And, I must admit that junction pools can give me fits! This is especially true when the junction is created by a substantial tributary entering the main stem of a creek.

For example, I have fished a junction pool numbers of times where a specific larger trib meets Spring Creek. This tributary adds a large volume of water to Spring. The pool created is a round bathtub with a rotating current. For example, there is a spot where the pool currents actually move upstream on Spring Creek. I know for a fact that that pool holds big fish. Likely even a monster lurking in there. Nevertheless, I have never caught a fish at that junction.

On smaller junction pools, where the entry is more parallel than perpendicular, I like finding the soft seams created where the corresponding currents join as a result of friction. These are often noticed as a slower moving top current and the substrate here tends to be deposits of gravel or sand. I tend to stay away from the heavy and deepest part of a junction pool. Even though this appears to be the juiciest water available.

Picking these shallow, soft seams apart with a single lighter nymph on a wild trout stream often rewards me with hookups with average sized fish. However, taking a careful approach to wade into position and fishing close and upstream is a necessity. This slow and deliberate presentation is a must.

Thank you, Ralph, for teaching me more about junction pools and helping me learn new approaches. I need to read this post more and more, over and over and institute the lessons into practice on the water.

Justin

Hey Justin,

Thanks for taking the time to comment! Really glad you found the post helpful. I’ve always struggled with junction pools, too. They’re tricky, and like you, I’ve definitely come across those pools where I just cannot seem to catch a fish, despite knowing that there has to be a bruiser in there! Sometimes it takes a mayfly hatch to show you just how many fish are holding in some of these pools!

I agree completely about streams entering more parallel with each other. First Fork and East Fork are a prime example. The current is more predictable here, but it’s not usually where I find the biggest fish. The biggest ones always seem to be tucked against those hard-to-reach underwater ledges.

I see you also commented about the pink fish in the graphic in the post. Yes! Those spots are almost always productive, especially on heavily fished streams. I feel like most people head right for the deep water and forget about those corners. Many times, the trout may not be sitting in those shallows, but they’ll stage just off to the side in the deeper water and swim out and nab anything that drops into those shallow, slower moving spots.

Thanks again for taking the time to comment! Always great to get feedback on this stuff and learn how others like to approach these waters, too!

Ralph