The Mickey Finn: An Effective Streamer with a Unique History

My first cast with a Mickey Finn almost caught a 20-pound Atlantic salmon. I use the term “almost” very loosely here. What really happened was that the fish turned toward the fly, inspected it, and quickly deemed it unworthy. According to my friend, an Atlantic salmon fanatic, no matter what else happened from there on out, we’d already had a damn good day.

For that reason, I keep a handful of Mickey Finns in my streamer box, not only to remind me of that day, but also that success can be measured in many ways, and it means something different to each individual person. Sometimes I tie on one of those Mickey Finns for sentimental reasons, and other times because I want to catch fish.

The Mickey Finn is right up there with the Royal Coachman as far as being one of the most recognizable flies in the world. It’s a simple but effective streamer pattern, derived back in the days when fishing streamers for trout and other species was a brand new concept.

History of the Mickey Finn

For many years, there was debate over who actually invented the Mickey Finn, but most agree that credit goes to Canadian fly tyer Charles Langevin, who first tied the fly in the mid-19th century. The eponymous “Langevin” was later referred to by outdoor writer John Alden Knight in the 1930s as the “red and yellow bucktail,” presumably because he didn’t know who’d created the fly. In fact, for many years, nobody knew exactly who was responsible for inventing the Mickey Finn, and it may be debatable even today.

While a fly called the Langevin was proven to exist in the 1800s, there’s some doubt about whether this fly was indeed the same one that later became the Mickey Finn. The Langevin was described in Thaddeus Norris’s 1864 work, The American Angler Book, as having “Wings, body, tail, hackle, legs tip all yellow; made of dyed feathers of the white goose; the head of black ostrich and the twist of black silk” (The American Fly Fisher, Fall 2015).

No mention of red in the wing. Also, the fly described in Norris’s book is a featherwing pattern, not a bucktail pattern. However, keep in mind that Norris, although reliable by all definitions, was providing this description as secondhand knowledge, as the fly comes via Dr. Adamson who provided Norris a list of flies known to catch salmon in Canada.

Of course, this is not uncommon when discussing classic fly patterns, as flies were handed down and passed around like old stories. Over time, those stories become bastardized and changed so much they barely resemble the original tale. We see that in even today’s world of fly tying. The main exception is that today’s tyers seem more eager to change one material on a fly and claim it as a whole “new” pattern, which they quickly name after themselves.

Whether the Langevin was the same fly as what became known as the Mickey Finn or served as its inspiration is perhaps irrelevant. The final say seems to lie with the Canada Post, which released a series of stamps in 2005 that included four classic fly patterns: the Alevin, Jock Scott, Mickey Finn, and P.E.I. Fly. In the description provided with the pamphlet accompanying the stamps, the Canada Post credits Langevin as the Mickey Finn’s creator. As Jan Harold Brunvand writes in the Fall 2015 issue of The American Fly Fisher, “Now if only we could discover where the post office got its information!”

How the Mickey Finn Got its Name

More interesting (to me, at least) is the name of the fly itself. How did the Langevin eventually become the Mickey Finn? That history lies firmly with John Alden Knight, a writer and fly tyer from the Catskills who is credited with developing the Solunar Tables.

Knight, an early proponent of the “red and yellow bucktail,” renamed it the Assassin in a letter to Joseph D. Bates, who would later author the book “Streamer Fly Tying and Fishing” (1966). As legend has it, in the late-1930s, Knight wrote about the Assassin in an article in which he recounted a conversation with fellow writer and fly fisher Gregory Clark. Clark had jokingly referred to the streamer as a “Mickey Finn.”

The real Mickey Finn was a saloon keeper from 1896-1903 along what was known as Whiskey Row on State and Harrison streets in Chicago. Finn owned the Lone Star Saloon as well as the Palm Garden and was known to concoct a special drink of raw alcohol mixed with unidentified powders. It was potent, rendering all who drank it unconscious on the bar. While a patron was knocked out, Finn would rob him and dump his body in an alley near the tavern.

According to the website Chicagology.com: “But on December 16, 1903, Mayor Carter Harrison ordered the closure of the Lone Star Saloon, and Mickey Finn wisely left town shortly thereafter. But not before he sold the formula for his famous drink to a number of other Southside saloons, who marketed it as a ‘Mickey Finn,’ or even just a ‘Mickey.’ The name eventually came into use as a generic term for any knockout drink, and to ‘slip a mickey’ into someone’s drink now means to secretly drug an unsuspecting victim.”

Two Reasons to Try the Mickey Finn

The first reason, of course, is because it catches fish. A hundred and eighty years later, we’re still using it to catch trout, pike, salmon, and many other species. But I do believe there is a “sweet spot” when the Mickey Finn works best. I primarily use streamers such as the Mickey Finn when streams are off-colored or murky. Of course, that doesn’t mean this fly is simply a niche pattern. I’m sure it would work during other conditions, but when the water is clear, I tend to select more natural and subdued colors to fish with.

The Mickey Finn has great contrast, like many ultra-effective patterns. In this case, that contrast comes via the red and yellow bucktail used to create the wing. For me, this also serves as even more proof that the fly was developed by a Canadian – Lengevin hailed from Quebec, which is prime country for brook trout, lake trout, pike, and Atlantic salmon. Many of the lakes and rivers in Quebec, especially those in the boreal forests and wetlands, are tannic in color (tea-colored or brown) due to natural tannins leaching into the water from plant matter. In such conditions, bright-colored flies with contrast can be deadly, and in my own experience fishing similarly-colored waters, yellow and red perform exceptionally well.

The second reason to use the Mickey Finn is that it’s easy to tie. It requires only a few materials and, with practice, can be whipped up in just a few minutes. It’s a great pattern for beginners and experienced tyers alike. And it’s a fun fly to tie and experiment with.

Perhaps the true tribute to a fly’s effectiveness is the number of variations it inspires, and the Mickey Finn is no different. I’ve seen this fly tied in dozens of different ways, using different materials for the body and/or wing, some with painted-on eyes and some without. In my opinion, the primary trait of a “Mickey” is the combination of colors: red, yellow, and silver. Any time we tie a silver-bodied fly with a red and yellow wing, we’re paying homage to the Mickey Finn.

Tying the Mickey Finn

Materials Needed:

Hook: 4X-5X long streamer hook (sizes 6-12 work well). For this pattern, I really like the Mustad R75AP, which is 2x heavy and has a 5xl long shank.

Thread: Black 6/0 or 8/0 Semperfli Classic Waxed Thread.

Body: Silver flat mylar tinsel (some variations call for gold tinsel).

Ribbing: Silver Ultra-Wire (optional) or Silver Oval Uni-French in Medium size.

Wing: Yellow bucktail, red bucktail, and another layer of yellow bucktail.

Head: Black thread (optional varnish or head cement for durability).

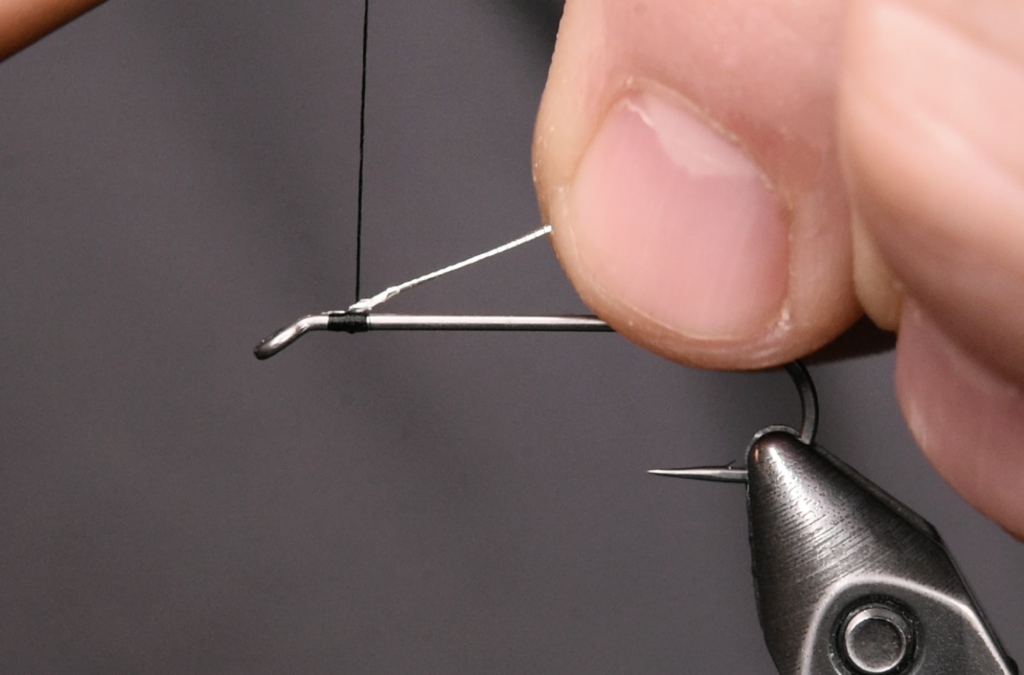

Start the thread slightly back from the eye of the hook. I like to leave a 1/8-inch gap between the hook eye and the thread as a reminder of where I want to tie in the butt sections of the hair wing. When tying in three different layers of material, it can be easy to crowd the hook eye.

Tie in a length of ribbing wire (optional) near the front approximately where the body will end and wrap a thin base later of thread along the hook shank back to the bend of the hook. Tying near the front of the fly will help create a more even body. Tying in the rib near the bend of the hook will typically produce a lumpy butt.

Near the bend of the hook, attach a length of mylar tinsel with gold side facing up. Advance the thread up the hook shank to create a thin, evenly-wrapped body. Wrap the mylar up the hook shank with silver side facing up and secure with thread. Next, counter-wrap the ribbing over the mylar body and secure and trim excess wire.

Cut a small bunch of yellow bucktail and tie it in just behind the hook eye, ensuring it extends slightly past the hook bend. Use pinch wraps to hold it in place on top of the hook shank. Cut and stack a slightly smaller bunch of red bucktail and tie it directly on top of the yellow layer. Finish with another small bunch of yellow bucktail on top of the red layer, creating a well-balanced, layered wing.

Wrap the thread neatly around the base of the wing to secure all materials and create a solid black head. Whip finish and coat threads with head cement or thin UV resin. This will create a neat looking head while also holding the materials in place and make the fly more durable.

Have a fly fishing question you’d like answered? Drop us a line at info@darkskskiesflyfishing.com! If we use your question in a blog post or in the newsletter, we’ll send you a FREE fly box with a dozen of our favorite nymphs and dry flies!

I enjoyed this article thoroughly, Ralph, because the first trout I had ever caught on a fly was with a Mickey Finn.

Really glad you liked it, Justin! The history of certain flies has always interested me, especially classic patterns like the Mickey Finn.

Me too Justin

. Close to 60 years ago..A 14 inch brookie in a small mountain stream and I reverently released it. Iwas hooked ( pardon the pun ) on fly fishing ever since. The MF & Hornberg became my 2 favorite flies and still are.

Tight Lines…Kerry

Kerry, 66 years ago when I was 16, I caught my first 2 trout, rainbows, opening day weekend on The Big Flat Brook in NJ on a Hornberg dressed with Mucilin to make it float.

Here is some other info on the Mickey Finn.

At the Sportsmen’s Show in the Central Palace (in NYC) in 1937, between a quarter and a half million Mickey Finns were tied. There was not a red or yellow bucktail to be found in any shops in the area. Each night bushels of red and yellow bucktail clippings were swept up from the floor. Also, during the first two to three month period in 1938, The Weber Company (originally Carrie Frost’s old company, C.J. Frost Fishing Tackle manufacturing Company) in Stevens Point, Wisconsin produced 1 million Mickey Finns, stretching their tying staff to their limits.

The original fly did not feature the separation of the colors as does the modern version, but it was close.

As an aside, I caught my first northern (about 36 inches long) on a Mickey Finn while trout fishing at Fisherman’s Paradise on Spring Creek in Pennsylvania.

That’s a really neat story! Just one of the reasons I love old patterns. They always have a lot of interesting anecdotes behind them. Thank you for sharing that, Bob!