Winter Fly Fishing Tactics for Trout

Winter fly fishing has changed since I was a teenager. Thirty years ago, when you fished during the winter months, you could expect to have streams all to yourself. Long sessions on the water might end without ever seeing another soul. These winter experiences were special and provided long hours of solitude and reflection, and yes, maybe even some dreaming about warmer days, and although I always seemed to catch a few fish, each one was hard earned.

A lot has changed since then. Now, some winter days, I see so many other anglers you’d think it was prime time in the spring. Winters aren’t as severe as they used to be, which means more opportunities to be outdoors. Even where I live in northcentral Pennsylvania, the snow doesn’t get as deep, and the sub-freezing stretches don’t seem to last as long. We have more mid-winter thaws, more unseasonably warm spells. And this phenomenon isn’t exclusive to these traditionally “my God, it’s cold out there!” parts of the country; it’s happening everywhere.

Sure, there are exceptions, and every once in a while, we still get some normal winter weather. According to the Pennsylvania Environmental Council, in 2023, “North America had its warmest December on record. In Pittsburgh, the average winter temperature has risen 4.4 degrees since 1970, according to data compiled by Climate Central, an independent nonprofit comprised of leading scientists and journalists. In Philadelphia, the average is 5.5 degrees warmer. Such a trend is making winter recreation difficult.”

It might be a bad time for ice fishing and skiing, but for fly fishermen, this warming trend has provided an opportunity for year-round angling. Streams and rivers in most regions (except for the far north) simply don’t freeze over as long, if at all, like they used to, and open water can be found in most regions of the country all 12 months of the year.

In fact, these might just be the glory days of winter fly fishing. The weather is just cold enough to keep many “fair weather” folks at home and warm enough that conditions are tolerable and you can experience some really phenomenal days on the water. But there are a few tactical changes you can employ to improve your winter fly fishing success.

Tactics for Winter Fly Fishing

My overall setup doesn’t change much from season to season. Rather, it changes according to conditions. In this region of the country (Great Lakes Region), we’ve had excellent water flows throughout winter the past few years. Some of our best overall fishing conditions, in fact, have come during winter. But as with other times of year, when flows are high and heavy, I use heavier rods and tippets. When water is low and clear, lighter rods and tippets are the norm.

A Careful Approach – Move slowly and use in-stream structure to mask your approach and get closer to your target.

More than anything, your approach can dictate success or failure when winter fly fishing. When rivers and streams are flowing at “average” levels and clarity (whatever that is on your home water), trout will be most skittish in the winter. Most if not all of the foliage is off the trees. Ground cover is beaten down. Plant particles in the water are mostly gone. The water is as clear now as it will be any time of the year. There’s nothing to shield your approach.

Translation: every move you make is visible to the fish!

I’m convinced that most winter anglers don’t spend enough time considering their approach. The tendency is to wade in there and start making casts. I believe more trout are spooked by anglers getting into position to cast than most will ever realize, not just because of being seen by the fish, but also from being heard.

A rule of thumb that I like to follow is this: if I can hear myself wade, then the trout can hear me, too.That goes for any time of year, but it’s even more important to keep in mind in winter. Whether it’s the push of water or the sound of studded boots ticking on the river bottom, trout can hear us coming from farther away than we realize.

Trout are no different than any other wildlife, and each individual has its own tolerance to human encroachment and activity. However, when there’s nothing to visually mask your approach, factors such as the noise you make becomes that much more important.

Selecting Fly Size and Weight – The common advice is to select small fly patterns for winter fishing. It’s good, logical advice. After all, most of the food available to trout this time of year is small. Midges, immature mayfly nymphs, etc. But larger nymphs work, too. Think about it. If you bump a trout’s nose with a big stonefly nymph, is it going to refuse the fly because it’s too big? Absolutely not!

As with other gear you use (rod weight, tippet, etc.), fly size should be dictated by the conditions. Low and clear typically means smaller flies in more natural colors. High and off-color usually means larger and brighter patterns. There are two primary factors to keep in mind during fly selection:

- A trout has to be able to see your fly in order to eat it. This is why bright colors typically work well in off-color, dark, and tannic-colored water.

- Water speed and depth. Rather than think of it in terms of fly size, I prefer to think of it in fly weight, a.k.a. bead size. Faster and deeper water requires a heavier fly to get down as well as slow my fly enough to put it in the strike zone long enough for the fish to eat. Most of the nymphs I use range between sizes 12 and 20, with the bulk of them being sizes 14-18. But I tie every pattern in multiple sizes and with varying bead sizes so that I will have what I need no matter what conditions I’m presented on the river.

Here’s an article that discusses some of our favorite patterns for winter fly fishing.

Fish Slower Than Normal – Trout feed less aggressively in cold water, but they don’t stop feeding, which we’ll discuss in a moment. However, their slower metabolisms mean they can be sluggish, and sometimes you really do have to bop them on the nose with the fly to get them to eat.

This is easy in smaller, shallower streams where the prime lies are easily identified and it’s a simple matter to get your presentation exactly where it needs to be within the first couple of drifts. On larger rivers, though, I tend to take more time and fish spots a little longer than usual to make sure I’ve given the trout a chance to see and eat my fly.

Even on smaller streams, though, I tend to work slower in the winter and make a few more presentation changes before moving on. If I’m not catching fish, I assume it’s because my presentation is off, not because fish aren’t hungry. The first thing I do is adjust weight, either by adding or subtracting a split shot, if I’m using one, or bumping up or down in bead size.

The next adjustment is drift speed. More fish are “not caught” because the fly is moving too fast than too slow, particularly in the winter. Drifting your flies as slowly as possible through prime lies will increase your chances of success

Streamers/Large Flies – Streamers and other large flies will still catch trout in winter, but don’t expect trout to chase them like they would at other times of year. Often, I’ll use a weighted Woolly Bugger (sizes 6-12) and use 1-inch strips to crawl it along the bottom of deep pools. This can be amazingly effective, but the retrieve has to be painfully slow.

In swifter sections of river, I dead-drift the same Woolly Buggers, and sometimes even larger streamers. This isn’t a high numbers tactic, but it occasionally produces a very large fish.

If you really want to cast and retrieve streamers, you can still catch fish in the winter. But again, the retrieve has to be slow. I often land the fly behind structure and wait a full second before making the first strip. This allows the fly to sink a little bit, but also gives the trout time to react. In the winter, when fish are more sluggish, three or four strips of the fly (as soon as it’s out of the prime holding water) and I’m already pulling it up out of the water for the next cast. There’s no sense stripping it all the way to the boat or to your feet because of the trout’s lack of motivation to chase this time of year.

When Do Trout Feed in the Winter?

There are many myths about when trout feed (or not) in the winter, and it’s important to address them because they can impact your expectations. I’ve often said that the mental game is often the biggest part of any skill, and what’s going on between your ears absolutely effects how well you perform in any sport – baseball, basketball, etc. In fly fishing, the mental game is just as important because it influences how well you fish. So if you believe that trout don’t feed in the winter because the water is colder and their metabolisms are slower, that will ultimately shape how you view winter fly fishing. You’ll expect low success rates and slower days on the water.

Read this article to learn more about the Mental Game of Fly Fishing.

Trout Still Have to Eat – Long ago, many anglers believed trout rarely fed at all once water temperatures dropped into the 30s, and I suspect many still feel that way. But a trout must feed in order to survive. That’s an important thing to remember, always.

Sure, sometimes trout just shut down. A dropping barometer, an incoming cold front, or other weather changes can put trout down and there’s just nothing you can do about that. They move to the bottom of deeper pools for protection and rest, and these fish can be quite difficult to persuade to bite. But I can assure you that at some point every day, trout will eat.

Feeding Windows – While it’s true that feeding windows can be shorter in the winter than other times of year, those windows of activity can be incredibly intense. Recently, while fishing the Clarion River, I hit a feeding window that was absolutely incredible. For about 45 minutes, I caught trout on almost every drift. It felt like, during that brief period, every trout in that riffle was up and eating. And then, as quickly as they turned on, the trout shut off. Later that afternoon, around 3:30pm, they turned back on again for a short time, but the feeding wasn’t nearly as aggressive.

I avoid arbitrary numbers, though, such as “you should fish between 10am and 3pm.” I can’t even count how many times I’ve read articles by experts saying you should fish during this time frame in the winter. If you’re looking for numbers of fish, or if catch rate per hour of fishing matters to you, then yes, you may want to focus your efforts on fishing only the nicest parts of the day during the winter. That will work for you the majority of the time. But in my experience, feeding windows can be hard to predict in the winter, and sometimes the best fishing comes when you least expect it.

Truth is, any time you can get on the water is a good time to fish. I’ve caught just as many big wild browns at the crack of dawn on a 32-degree morning as I have at high noon. In fact, I think many of these larger, wary fish prefer to feed before the sun hits the water or after it has set, regardless of time of year, air temperature, or water temperature.

Winter Structure and How to Fish It

The basic rule of thumb for winter fly fishing is to focus on water that is slow and deep. Specifically, I look for slow and deep water off the edges of faster water. The main current of the stream or river still carries the food, and a feeding trout will stage in the prime locations that allow it to capture that food while expending the least amount of energy.

It’s no different than any other time of year except that trout may position themselves in slightly slower water than they would in warmer months. During prime time in the spring, those same fish will hug that faster seam, moving in and out to aggressively intercept food. During the winter, they’re more likely to sit back a bit from the faster water and let the food come to them.

Deep Pools and Runs – These are typically the bread and butter of winter fly fishing and provide the best habitat for winter trout survival. Trout move into deep water habitats to find more stable conditions and slower currents. This is also where the bulk of their food can be found this time of year – crayfish, baitfish, etc.

I typically Euro nymph or tight line the riffles coming into these deep pools and runs, right where the riffle starts to deepen and drop off into the run or pool. During prime feeding times, trout still tend to move up into these shallower areas to feed, same as they do any other time of year, but they’ll do so for shorter periods of time, hence the shorter feeding windows common to winter fly fishing.

So early in the morning, I do tend to focus on deeper water. As the sun hits the water and water temps bump up slightly, aquatic insects get more active, which in turn gets trout more active. This is when I shift focus from the deeper pools to the shallower runs and riffles. Later in the afternoon, as air temperatures start to drop, fish will recede into those deeper hideouts again.

Fishing the “belly” of a deep pool or run, where the water is ultimately much slower, often requires the use of an indicator. As soon as the nymphs hit the water, I throw a big mend that positions as much of the fly line as possible upstream of the indicator. The goal is to have the indicator lead the flies downstream to achieve a drag-free drift. When the fly line leads the indicator, drag is inevitable, and so your flies will be moving faster than the current, and often they will accelerate out of the strike zone before you even get to where the fish are feeding.

You can read more about mending and fishing with indicator rig in this article.

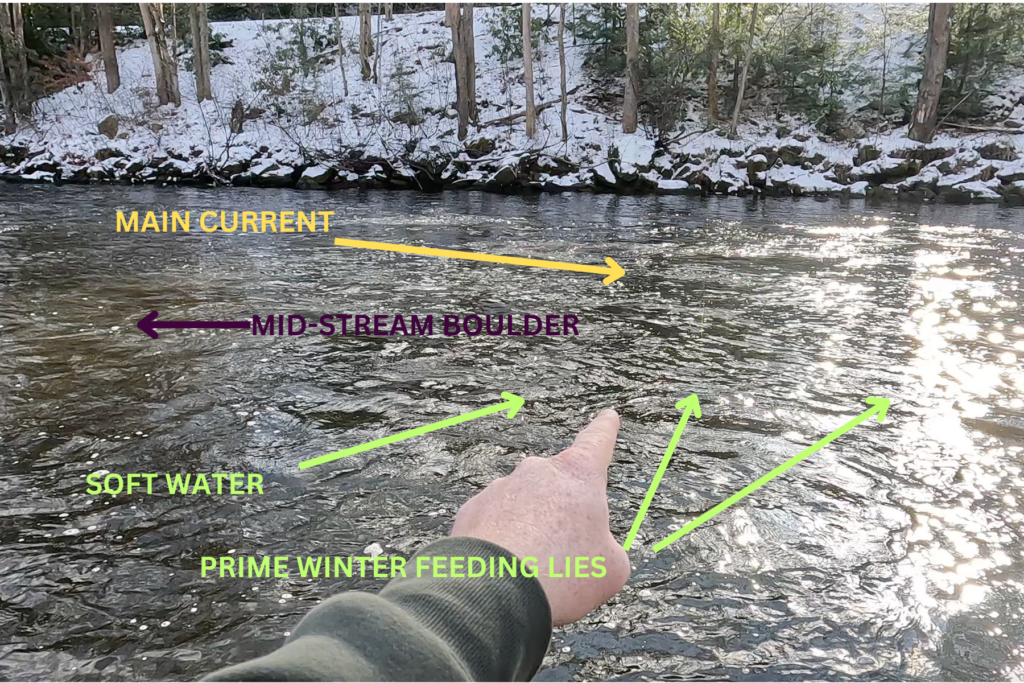

Mid-Stream Structures – Reading the water this time of year, I look for the breaks in the current, such as slow pockets behind boulders. In bigger rivers, especially, fish tend to pile up in these deep pockets behind large rocks.

To get your flies to these fish, cast up into the faster current and guide your presentation down into the slower water. Pay close attention to your sighter or strike indicator (whichever you prefer to use) as the flies approach the tail end of the pocket. Feeding fish often stage here in the slow water right before the faster currents come together again. This is the prime feeding lie because trout basically have two faster seams pushing food into this slower position of the pool, essentially doubling their opportunities for food.

Soft Spots in the Fast Water – Trout will also congregate in areas where conflicting currents come together to form soft spots. These soft spots can occur in even the fastest water, but where multiple conflicting currents collide, they neutralize each other and create a prime feeding lie. Again, I believe trout like to station here because of multiple food streams coming at them, and maintaining their position in the current requires little effort.

Sometimes these soft spots are only a foot or two long before the currents straighten out and pick up velocity again. The hard part is getting your flies to the fish in these locations. Typically, this means adding more weight (split shot) or choosing heavier flies or even casting a little farther upstream to ensure your flies are in the strike zone by the time they reach the soft spot. But more importantly, you want to be able to almost stop your flies once they reach this spot. This can be done with a big mend (if using an indicator) or by stopping your rod (if tight lining) and allowing the flies to fall directly under your rod tip. This will slow your presentation down and enable it to linger in that soft water an extra second or two, which can be enough to trigger a strike.

Bank Water – The first few feet of water off the bank can be a prime lie for feeding fish in the winter, particularly if there’s some sort of structure present. This can be an undercut bank, rock ledge, overhanging tree, or any number of objects that provide some form of security for the trout. And it doesn’t take much. Many times, I’ve found a rotted, water-logged tree limb lying parallel to the bank in only a foot of water and have been surprised to find a trout shoot out from under it as I waded to shore. It has happened so many times, in fact, that I now fish those spots before plowing through them, and it’s surprising how many trout I’ve added to my day.

Some of the best bank water, I’ve found, is where there is overhead structure (a bush, for example) and sunshine on the water for a couple hours a day. This slightly warmer water, I imagine, feels awfully good to trout in the wintertime, and they often stage here to feed.

Here’s a video we did on Yellow Breeches Creek last winter. In this video, you’ll see a prime example of how to fish bank water and the surprising results it can produce.

Winter Fly Fishing on Small Streams

Small streams are much easier to fish than big rivers, especially in wintertime. The prime lies are more easily identified, and it’s easier to get your presentation to where the fish are. If you’re having trouble catching fish on larger waters, spend a day on a smaller stream and build some confidence. Small streams are just microcosms of big rivers. Everything that happens on small streams happens on big rivers, and everything learned on them can translate into success everywhere else. There are a couple differences, though, in how I fish small streams in the winter.

Dry Dropper Rig – Rather than use a strike indicator, which sometimes can cause a disturbance when it lands on the water, I opt for a dry dropper rig. In this case, the dry fly acts as the indicator more than it’s intended to catch fish. Every now and then a trout will take the dry, but most winter fishing I do on small and large waters is subsurface.

Any big, bushy dry fly will do. I’m particularly fond of Chubby Chernobyls and other foam-bodied flies because of how well they float, and they can support heavier nymphs, if needed, to fish bigger, deeper pools in small streams.

Stay Out of the Water – Remember how I mentioned that most trout are spooked on the approach? That’s especially true on small streams, where fish can sometimes even feel the vibrations of your footsteps as you get closer. Those vibrations are felt up through the stream bed if you’re wading, too. For this reason, I only get into the water if I absolutely have to in order to fish it right, or if I know I can wade into position quietly and without spooking trout.

Dress for Success

The little things make a difference in fly fishing. More time on the water means more casts made, which, hopefully, means more fish caught. It’s hard to feel optimistic and put in the time if you’re freezing your butt off. It’s imperative to have a good system for staying warm on the water this time of year.

For me, comfort on the water begins with my feet. I don’t have any special, insulated waders, but I do wear two pairs of socks, a regular pair of socks with a pair of heavy wool socks pulled over them. Usually this is enough to keep me going, but if I need more warmth, I stick a pair of toe warmers into my boots.

Keeping my body warm is all about layering. My “base layer” is generally a pair of athletic pants and a t-shirt. I wear a pair of sweat pants over the athletic pants, and a long sleeve shirt and a hoodie over top of the t-shirt. I finish it off with a fleece vest. This keeps the bulk down on my shoulders and arms so that my casting isn’t inhibited in any way.

If it’s really windy or bitter cold, I add a windbreaker to my attire. The windbreaker isn’t breathable, and it does an excellent job of holding in my body heat without adding bulk.

This “system” has kept me on the water through some pretty rough weather, but just because this works for me doesn’t mean it will work for you. We’re all different as far as how we tolerate cold weather. My advice is simply to find what keeps you warm, mobile, and comfortable so that you can fish longer during the winter months.

For me, the real secret to getting more time on the water is staying dry. Be careful when wading, mindful of foot placement, particularly if you’ve been stationary in cold water for a while. It can take a moment to get the blood circulating again and be able to feel the river bottom. Move slowly. Don’t take chances.

Final Thoughts

I truly enjoy winter fly fishing for trout. It can be a great time of year to fish those rivers and streams that usually receive a lot of attention in the spring. But more than that, any time of year is a good time to get outdoors, and more people are starting to realize it, too.

Warmer winters, less snow, and more open water have provided increased opportunities for year round angling. I have no doubt we are entering the golden age of winter fly fishing.

Did You Find This Article Helpful?

Stay up to date with the Dark Skies Fly Fishing monthly newsletter for free and receive the latest posts in fly fishing news, tricks, tips, and techniques, stream reports, as well as updates on new flies added to the Online Store and exclusive discounts!

Sign Up Now

Lots of good info Ralph. Thanks for sharing.