Trickle Trout: Tiny Streams Offer Big Surprises

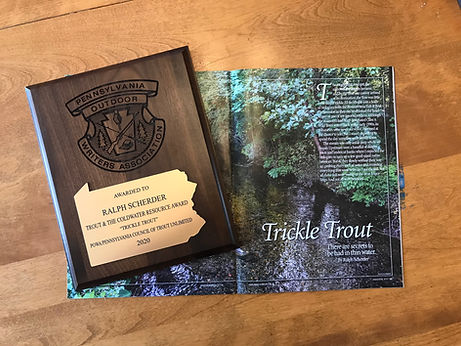

I’m pleased to announce that my article “Trickle Trout” which appeared in the March/April 2019 issue of American Angler recently received the Trout and Coldwater Resource Award, sponsored by the PA Outdoor Writers Association and Pennsylvania Council of Trout Unlimited. Although American Angler has since ceased publication, I’ve decided to post the article, in its entirety, here for your enjoyment. Also, I’d like to include some of the photos that didn’t make it into the print version due to lack of space.

Trickle Trout

The rougher the road got, the narrower the stream became, and by the time our convoy arrived at its destination, the flow was little more than a trickle. I’d decided to join a team of biologists from the Pennsylvania Fish & Boat Commission as they electroshocked the headwaters of one of my favorite streams. Although the main stem had been designated Class A Wild Trout waters back in the early 1990s, the tributaries that converged to create the stream had never been surveyed. I jumped at the chance to join them, but I wasn’t expecting to spend the day sampling such skinny water.

The stream was only ankle deep where we began. Upstream were a handful of deeper pools and undercut banks where I expected they’d turn up a few good-sized native brookies. But as they slowly worked their way up, probing every inch of water and recording everything that went belly-up, I got excited. Not all of those fish were young-of-the-year fingerlings. And not all were brookies.

When one of the biologists prodded a small plunge pool under a fallen log and a beautiful 18-inch wild brown trout came floating up, my jaw dropped. To me, it was impressive. To the biologists, who survey small streams often, this was typical.

By the end of the day, I’d gained a new appreciation for those little trickles and their ability to harbor fish. And I realized that many of the tiny streams I’d taken for granted for so many years probably held some nice wild browns, too.

Finding Fish

The area we surveyed had received a good bit of rain the previous week, but the stream was still barely six feet wide. As the biologists worked the water, I tried to anticipate the quality of fish we’d find. There wasn’t one pool that really tripped my hot button or looked like it might hold anything other than a scattering of tiny trout. Long, shallow riffles separated small, unimpressive pools. In short, it was the type of stuff you walk passed on your way to better water.

The beauty of trout, though, is that they are where you find them. At times they’re ferociously territorial and live out their lives within small quadrants. Other times they’re more transient than a band of gypsies.

PFBC biologists survey a small trout stream to determine if it meets Class A designation requirements.

Later in the afternoon, the biologists moved on to a second stream that had been surveyed the year prior. That survey had produced enough trout to warrant a reassessment to see if it would meet the requirements of a Class A water (40kg of biomass per hectare). One of the biologists was especially excited about the resurvey because he’d taken part in the first one which had produced healthy numbers of wild browns up to 20 inches long. Again, this stream was about six feet wide, and in many places narrower than that. Another trickle.

As the crew worked upstream, beginning at the same point they first surveyed, their findings were considerably different. All of those big fish were gone. They turned up a few browns in the 9- to 12-inch range, but none of the bruisers they’d anticipated…until they got to the really skinny, maybe three feet wide. Suddenly, every pool with a little depth and good structure produced a wild brown over 16 inches. “That’s a relief,” one biologist said. “I was beginning to think these fish were going to make a liar out of me.”

According to the team, this was normal. The reason they clip a sliver of caudal fin on every trout they capture is so that they know which ones they’ve caught before when they resurvey a section. They often find that fish caught even just the day before have relocated.

After spending a day surveying these trickles, I decided to assume until proven otherwise that a nice-sized brown lived in every little bit of holding water. When I applied that approach to the streams I fish, my catch rates went up and I started picking up bigger fish than I ever had.

I also realized that, in trickles, big trout don’t always utilize the most obvious holding water all the time. Watching the stream survey was fascinating in that deep pools, even ones with desirable undercuts and root systems, didn’t necessarily guarantee big browns and, in fact, were often void of fish.

That doesn’t mean these pools went unused; lunker trout spend the majority of their time around other structure and move into the deeper pools to feed. The catch, of course, is that you never know when they’ll decide to feed, which is why it’s best to assume they’re always present.

In trickles, the holding water trout prefer is the kind that’s almost impossible for anglers, or other predators, to approach without being seen. It doesn’t have to be deep, but it must have structure that trout can slip under (usually long before you even get to make a cast).

During my time following the survey crew, the most surprising find came in a stream only three to four feet wide and in a pool less than calf deep. When they probed a narrow gap under an overhanging rock, a hefty 16-inch wild brown floated into their net. I couldn’t believe that a trout of that size could thrive in such skinny water. It was the equivalent of finding a 50-inch musky in your bathtub.

The Trickle Factor

The question that should be asked is, do trout live in trickles year-round? The answer, most likely, is no. In my experience, wild brown trout work their way into these diminutive streams during two occasions – when spawning in the fall (when water levels are up) and when seeking thermal refuge in the middle of summer. (Note: Although the air temperature approached 90 degrees Fahrenheit the day of the stream survey, the water temperature rarely exceeded 50 degrees F.) Wild brown trout in these heavily canopied coldwater sanctuaries are often overlooked by most anglers who think it takes big water to produce big fish. Therefore, it makes the most sense to target these trickles during those two times.

During summer, some trickles get so small that trout simply cannot work very far up into them due to natural barricades, such as waterfalls or long stretches of shallow water – and by shallow, I mean less than a couple of inches deep. Usually, if you find larger fish above natural barricades, it’s because they arrived there in the fall and were confined when water levels dropped.

But, as long as they’re trapped in a pool with enough overhead cover or structure and potential food sources, they’ll continue to thrive and grow. Also, just because the bigger fish are unable to navigate the stream doesn’t mean that young-of-the-year fry don’t still move around a bit. And when they end up in the same pool as a larger fish, they often end up in its belly.

Trickle Tactics

Knowing they’re there is one thing. Catching them presents a whole other challenge.

First of all, if you have to enter the water at any point, chances are you’re already beat. I never realized how many trout I was potentially spooking until I watched the stream survey. The reason they survey streams multiple times is because a percentage of fish evade their probes. Numerous times I witnessed trout bolting upstream, sometimes 10 yards or more ahead of the crew, that were long gone by the time the bios there.

The smaller the water, the more sensitive trout are to the vibrations on land, and especially to those on the streambed.

It’s helpful if you can spot the fish before making your first cast, but that’s usually impossible. In larger rivers, where the water depth itself is a form of structure, trout feel safe in the open. Trickle trout don’t have that luxury. Typically, anglers first see them as they bolt from under a rock, log, or some other structure to either take your presentation or vacate the premises.

That doesn’t mean you shouldn’t spend considerable amounts of time just watching the water. Sometimes you can pick up the slightest movement or change in shadows next to structure that indicate fish. It’s not uncommon to have trout move into and out of a pool you’re fishing, seemingly without rhyme or reason.

That said, I still don’t spend a lot of time at any one pool. Trickle trout are opportunists, and if I’ve covered the water effectively with just a few casts, I move on. Sometimes you have to cover a lot of water to locate big fish that are accessible. In truth, many wild browns living in these diminutive dwellings are simply uncatchable because of the lairs they’ve chosen.

I don’t fret over fly choice when fishing skinny water. However, I do use mostly weighted flies because I want them to get down quickly in those tiny pools and pockets. Mastering the art of the short cast is almost a prerequisite to success on these waters.

I have no preference when it comes to working up or down a stream. I prefer to walk well back away from the water and observe the pools from a distance, then approach and fish from the middle. My logic is this: If I start at the tail or head of a pool and spook trout, those fish inevitably spook other fish. If I start in the middle of a pool and spook trout in the tail end, then I’ve effectively cut them off and still have a shot at the ones at the head of the pool – and vice versa.

No other situation or conditions – or quarry, for that matter – test your skills at such a precise level. When you catch a nice wild brown, even if it’s not a monster compared to those found in much bigger rivers, you know you’ve done everything right. For me, chasing wild browns in trickles is an addiction. And it’s one vice I’ll happily encourage everyone else to try.

Great Article. Love fishing blue liners